There is an important difference between the study of ancient and modern musics. In modern music, we generally know what the music sounds like and how it is made; consequently, research focuses on the music’s structure, effects, or contexts; we can use the sound to understand broader issues. In studying ancient music, on the other hand, much research is an attempt to reconstruct the sound of the music itself.

For example, a modern researcher interested in Native American protest songs from the Standing Rock movement of 2016 might have access to notated or recorded versions of songs and lyrics; will speak or will learn to speak the necessary languages; can interview the singers or people who knew them; and will have access to oral histories and written records that allow them to explore the music’s relationship to its cultural context. A researcher who is interested in deciphering an ancient musical notation, on the other hand, will have to develop a sense of the sound of the music; will probably have to learn an ancient language without a community of people who speak it daily; and will strain to understand the music’s relationship to its cultural context.

In other words, research in ancient music is often reconstructive, educated guesswork that tries to make sense of the existing evidence. Legitimate scholars admit this openly; less credible authors will obscure the amount of speculation in their work, claiming to have definitively rediscovered lost works. Some of this hyperbole, of course, is simply marketing gone awry; it becomes dangerous when the scholars themselves believe it.

At the same time, all such research suffers from an important limitation: the urge to view all past music as something mirroring modern experience. Although we can imagine ourselves in well-documented periods of history, antiquity is something different—”the past is a foreign country,” as the old saying goes. The further that we go into the past, the more our evidence is fragmentary and capable of misinterpretation—and it’s only too easy to fill in the gaps with ideas that make sense to us, but which might not have made sense to ancient musicians. Two examples will suffice.

A clay tablet found in the ruins of the ancient city of Ugarit (near Ras Shamra, Syria) contains markings in an ancient Mesopotamian language known as Hurrian. Scholars eventually realized that these markings contained a religious text, which they labeled “Hurrian Hymn no. 6,” and musical notation for a lyre (a lyre resembles a harp, but it has a bridge like a guitar). This is, to date, the oldest surviving notated composition (c. 1400 BCE).

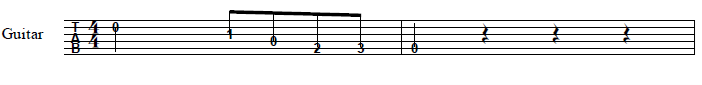

Hurrian Hymn no. 6 is written in a type of tablature, meaning that it consists of instructions about how one should play an instrument, rather than abstract descriptions of notes to be played. To better understand the issues involved, let’s first consider modern tablature (Example 1). Its six lines are a visual depiction of the six strings of a guitar. A guitar is typically held against your chest when you play the instrument. The topmost line represents the string that is highest in pitch and furthest away from the player’s chest, while the bottom line represents the string that is lowest in pitch and closest to the player’s chest. The numbers indicate fret positions on each string, showing how far up or down the neck of the guitar your hands should move, while the lines and beams suggest rhythmic values. This notation assumes standard guitar tuning (the strings are, from bottom to top, E2, A2, D3, G3, B3, E4). The system is not particularly intuitive to someone who does not understand the guitar or its tuning, but it is widely used around the world.

Now imagine that you had never seen a guitar, didn’t know how it is held, and didn’t have any idea what the pitch E2 is, and you are closer to understanding the problem of “Hurrian Hymn no. 6.” In studying it, scholars have had to discover all the things that we take for granted with guitar tablature. Detailed studies of other contemporary texts revealed the tuning systems used in music for the lyre—scales with seven notes. The tablature features an instrument with nine strings, which was probably a “bull lyre” of the type used throughout ancient Mesopotamia. The tablature itself consists of series of named intervals and numbers, rather than a visual map of the instrument’s strings. The intervals, however, are not named in abstract terms (such as the modern “perfect fifth”) but as combinations of strings: “first string and fourth string.”

Many scholars have attempted to decipher this notation, which undoubtedly made sense to musicians in Ugarit, just as guitar tablature makes sense to modern musicians, despite its peculiar qualities. To date, there is no definitive transcription of Hurrian Hymn no. 6; one point of debate is whether string 1 is higher or lower than string 2. In choosing how to interpret this ancient notation, scholars have not only considered the evidence, but also their understanding of how music sounded in the past. For example, West (1994, 179) argues that the Hurrian hymn must have been “rather plain by comparison with later…music” and probably resembled the surviving music of neighboring cultures. West’s transcription is thus quite simplistic in comparison to transcriptions by other scholars.

The music of the Jewish Tanakh or Bible poses a similar issue. Suzanne Haïk-Vantoura claimed to have uncovered hidden musical notation in the Masoretic text of the Tanakh and argued that the signs reflect a notated transcription of the music of the Temple in Jerusalem (destroyed 70 CE). Her theory focused on the interpretation of te’amim signs that accompany the book of Psalms, signs which rabbinical scholarship has long linked to both the punctuation of a poetic text and cantillation (the practice of singing chant from melodic formulas). Haïk-Vantoura’s theories attracted some attention on their appearance in the 1970s and 1980s, and still have supporters today, as her transcriptions are musically interesting.

The general scholarly consensus is that her work is faulty for two reasons. First, it relies too heavily on her own intuition—while her decision to use a seven-note scale reflects the practice of neighboring cultures in Mesopotamia, the specific choice of notes used in her transcriptions seems to be more influenced by her own taste than by research. Te’amim signs occur throughout the Jewish Tanakh, not just in the Psalms, and while they are used differently in the Psalms, there is much to learn from comparing their use in the Psalms with their use elsewhere. Second, unlike Hurrian Hymn no. 6, there is an existing community of people who are linked to these texts through oral tradition. While there is a diversity of interpretation present among Jewish cantors (trained singers of religious chant), none of their traditions match Haïk-Vantoura’s theory. Her work bypasses the rich tradition of cantillation (click on “complete haftarah” at the top right of the link for Jeremiah 46:13). It is difficult to believe that cantors and rabbinical scholars could forget the true meaning of their own craft—particularly since the Masoretic text of the Tanakh was created to clarify ambiguous passages in surviving manuscript copies of the Jewish scriptures.

Both Hurrian Hymn no. 6 and the Masoretic texts demonstrate the difficulties of reconstructing ancient music from surviving notation. It’s a bold thing to try to rebuild a musical world from fragments, and the temptation to bend the evidence to show the thing we want to find can be strong. Ultimately, these examples show us the limits of evidence and the ways that scholarship can fall into error.

Recommended Readings

Draffkorn Kilmer, Anne. “The Musical Instruments from Ur and Ancient Mesopotamian Music.” Expedition Magazine 40 no. 2 (1998). https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-musical-instruments-from-ur-and-ancient-mesopotamian-music/

A summary of Mesopotamian music by a leading scholar who helped discover ancient musical notation in Mesopotamia. You can read an interview with her, explaining her process of discovery here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Mitchell, David C. “How Can We Sing the Lord’s Song? Deciphering the Masoretic Cantillation.” In Jewish and Christian Approaches to the Psalms: Conflict and Convergence, edited by Susan Gillingham. Oxford University Press, 2013: 121–133.

Argues in support of Haïk-Vantoura’s interpretation of the Psalms, based on their musical quality.

Randhofer, Regina. “Singing the Songs of Ancient Israel: tacame ‘emet and Oral Models as Criteria for Layers of Time in Jewish Psalmody.” Journal of Musicological Research 24 (2005), 241–264.

Compares and contrasts contemporary Jewish chant traditions and their relationship to the surviving notated accents.

Werner, Eric. Review of Suzanne Haïk Vantoura, La musique de la Bible révélée (Paris, Choudens, 1978). Notes 38 no. 4 (1982), 923 – 924.

Criticizes Haïk Vantoura’s interpretation of the Psalms; summarizes evidence contradicting her central claims.

West, M. L. “The Babylonian Musical Notation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts.” Music & Letters 75 no. 2 (1994), 161–179.

Explains problems in interpreting the notation of Hurrian Hymn no. 6.